Floods in the British Isles: Peter Moir on the reasons for this “freaky” weather

Are you living in the British Isles? Even if not you must have heard about the severe floods we are currently suffering. In this article expert and author Peter Moir explains where all this water is coming from.

Peter Moir about “freaky” weather events

Rain, rain, rain and wet, wet, wet winter. This is not what I thought I would be writing about. In this one of my seasonal articles, I actually planned to talk about things that happen as the northern hemisphere cools for a few months. These plans were scuppered thanks to the weather across the British Isles.

Another of those “freaky” weather events is happening, just as happened when I was writing my book “A Wet Look At Climate Change (AWLACC)”. I started the book at the end of May 2009 and by the time I had written the last chapter about 2 months later in July, it was the wettest July on record.

Jumping forward to August 2012; I updated Chapter 10 of AWLACC with a global warming temperature chart and a cartoon by Matt of The Telegraph showing only the top of The Shard building in London above the floods. My comment was “Even where the temperature increase is only a small percentage, a small percentage of a very large amount of water is still a very large amount of water!”

Floods: “Worst in living memory”

Here I am again writing at a time where there are floods in Ireland not too far away from where I am sitting, and all over the UK. People in parts of Somerset now live in an inland sea. Comments appear on the news like “worst in living memory” and “unprecedented weather” etc., and we are left being grateful that we are not immediately affected.

As I have tried to bring out in AWLACC and in my articles, it is important to have data and grasp some of the science to really appreciate the consequences of global warming. It was not a risky prediction for me to make when I said in AWLACC that a warmer Earth will result in more severe weather. It is simply due to a physical relationship between temperature and moisture.

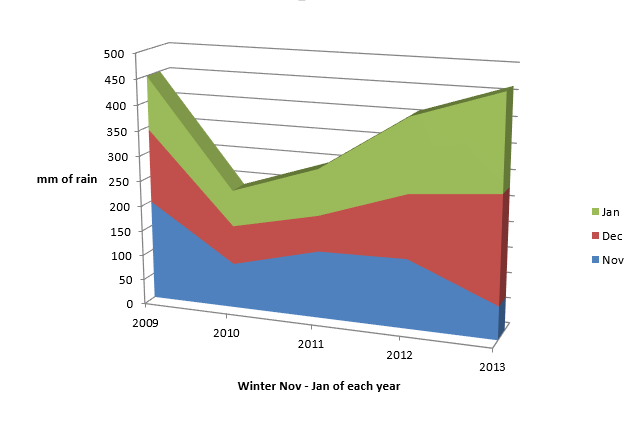

Readers of my book and blogs will know that in my garden I have a rain meter. Given the wet circumstances and everyone’s current topic of conversation, the bad weather, I have compiled into one chart my past five years of winter rainfall data.

The very clear dip in rainfall in the winter of 2010 was when we had the coldest and snowiest weather for 30 years. That’s when we lost our only two olive trees (Chapter 11, AWLACC).

What the chart does not show is the detail behind the statistics.

The consequence of the heavy rain

You probably will not remember, as it would not have been newsworthy, but from the second week in last November we went for about 4 weeks with hardly any rain. Look at 2013 on the chart and you’ll see a lower amount of rain than in 2009 -2012. Soon after, it started and just hasn’t stopped since!

Even though the total amount of rain on the chart this winter does not look much different from 2009, it is the distribution of rainfall that is the problem. Heavy showers followed by more heavy showers followed by persistent rain, and then more heavy showers.

I am writing this article on February 11th, just three days ago we had about 35mm of rain overnight from a storm that went on to hit the UK. That came after the previous weekend of 31mm over two nights. This has been interspersed with heavy downpours of 3 to 5mm and daily totals of 10mm or more. The ground is saturated and there’s nowhere for the water to go.

By the way, at the moment it is raining outside!

Autumn was not “autumnal”

Enough of doom and gloom, and back to my great plan that I mentioned at the beginning, well not that great actually, but it was a plan. An autumn blog was formulating in my head. Scenes of cool mornings, mist, and opportunities for taking photos and discussing moisture in the air.

Frankly, autumn was not “autumnal”, a favourite word of the weather people. Very mild and surprisingly dry! Instead of what I had planned for my latest blog article, I put together a series of photos of fungi that I had taken around my garden over a few years. I uploaded this to Slideshare if you would like to have look: Moisture, humidity and fungi.

But back to the original plan for my winter themed article.

Let me outline my plan

I was attending a course in Waterford and when driving past a field one cold morning I saw a very thin band of mist sitting absolutely still about four or five feet above the grass. The air below and above this band of mist looked fairly clear and it looked like it was magically suspended in mid-air.

My journey was timed to get to the course just before the start, so I had no time to stop and take a photo. I’ve of course seen similar patches of mist in fields but in this case the field was inclined up from road level so I could see underneath the band of mist.

My plan was to seek out another band of mist if the weather conditions looked right. You’ll have now spotted the spanner in the works. Maybe next winter…

Why bother, you may ask? Because it is curious and it interests me.

What appears as a static band of mist cannot be static. Water molecules in the air move at several hundred metres per second constantly colliding with other water molecules and the molecules that make up air. Therefore, there must be water molecules entering and leaving an apparently stationary band of saturated air (Chapter 2 AWLACC).

Not only did I want to get a photo, but, at the risk of trespass, use a temperature and humidity probe and, if possible, measure how much moisture there is in the air below and above the band of mist and explain this as a narrow band of temperature… or not.

Welcome to my world of moisture!

If you would like to delve deeper into the topic of climate change, then Moir’s free eBook “A Wet Look At Climate Change” is the right choice for you.